119: Green Hour

Hello, a warm welcome to Border Crossing issue 119, thank you for reading this and supporting my writing work during these daunting times. It means a great deal.

This issue, I offer four thousand and something words on art, sex and the extraordinary early life in Paris of the great painter Suzanne Valadon. No, you don’t have to read it. So long it’s almost a monograph.

Heads up: in March I’m putting prices up for Creativity Consulting, to try to fund a proper website. I’ve been relying on word-of-mouth and that’s ace but I ought to take it more seriously. So book in before the end of Feb to secure the current rate.

Also, in March I’m on a UK tour playing with Jim Bob. If you’re coming to a show, please come say hello.

The bubble of protection is a champagne bubble.

— me, on new year’s day

Right, let’s get on…

xx

gems

1

Stunning essay by Bee Wilson ‘Two Pins & A Lollipop’ for London Review of Books on the appalling, traumatised, fascinating life of Judy Garland.

2

I was floored by the BBC six-part drama series Waiting For The Out, a brilliant, intense, quite heartbreaking character study.

3

Your annual reminder to watch Nikki Glaser’s opening monologue at the Golden Globes and then her visit to Howard Stern’s show to share jokes she had to cut. Long may she reign.

4

Guillermo del Toro on This Cultural Life.

5

Mark Davyd (of Music Venue Trust) unpicks Margaret Hodge’s recent report on the Arts Council. He’s kinder, more measured, much politer than I would’ve been. Though in the end, Mark cannot help but demolish Hodge’s nonsensical ring-fencing of certain arts as if they are the whole of the arts.

For me, Hodge’s report had such flaws as to render it worthless. Mark doesn’t go that far, but does explain why, better than I can.

6

The important radical publisher PM Press is running a GoFundMe to purchase its warehouse in upstate New York for long-term stability.

spring courses

• Charlie Peverett of Birdsong Academy is running a ten-week online course called British Birdsong Essentials, starting 26th February.

• Award winning comedy writer and podcaster Joel Morris is running a podcasting crash course over two sessions in early February. Why on earth am I linking to this? The last thing I need is more podcasting competitors, in a shrinking diaspora, taught by one of the best out there. It’s like I’m gifting you a stash site in Battle Royale.

potato gem

• Sammy Gecsoyler in The Guardian on the resurgent comeback of the indie baked spud stall. Thanks a lot Charlie Ivens for nudging this one my way.

• Also note: in the Guillermo de Toro podcast interview listed above, he talks about his early Super-8 film about a potato serial killer. I’d love to share it but obviously can’t locate it.

•

Green Hour: on art, sex, labour and the early years of Suzanne Valadon

I wish participation in late capitalism on no one, it’s a horrifying state of affairs. But if I must participate — and I must, as a person who needs to earn money to live — I’ve always found it more interesting to search for modes of scam and subversion while offering myself up wholly to capital’s insidious demands, than to refuse. This is what, in part, drew me to sex work. This is what, in part, drew me to writing about it.

— Sophia Giovannitti

Note: there may well be errors. I’ve been trapped inside this one for days, juggling multiple (human) sources. Also there is sexual content.

Green Hour is a Belle Époque happy hour, the Parisian dusk drinking of a thriving artistic counter-culture, a late nineteenth century party scene with its many art and sex tourists. A gateway into Montmartre’s heady club life, Green Hour is named for the colour of absinthe.

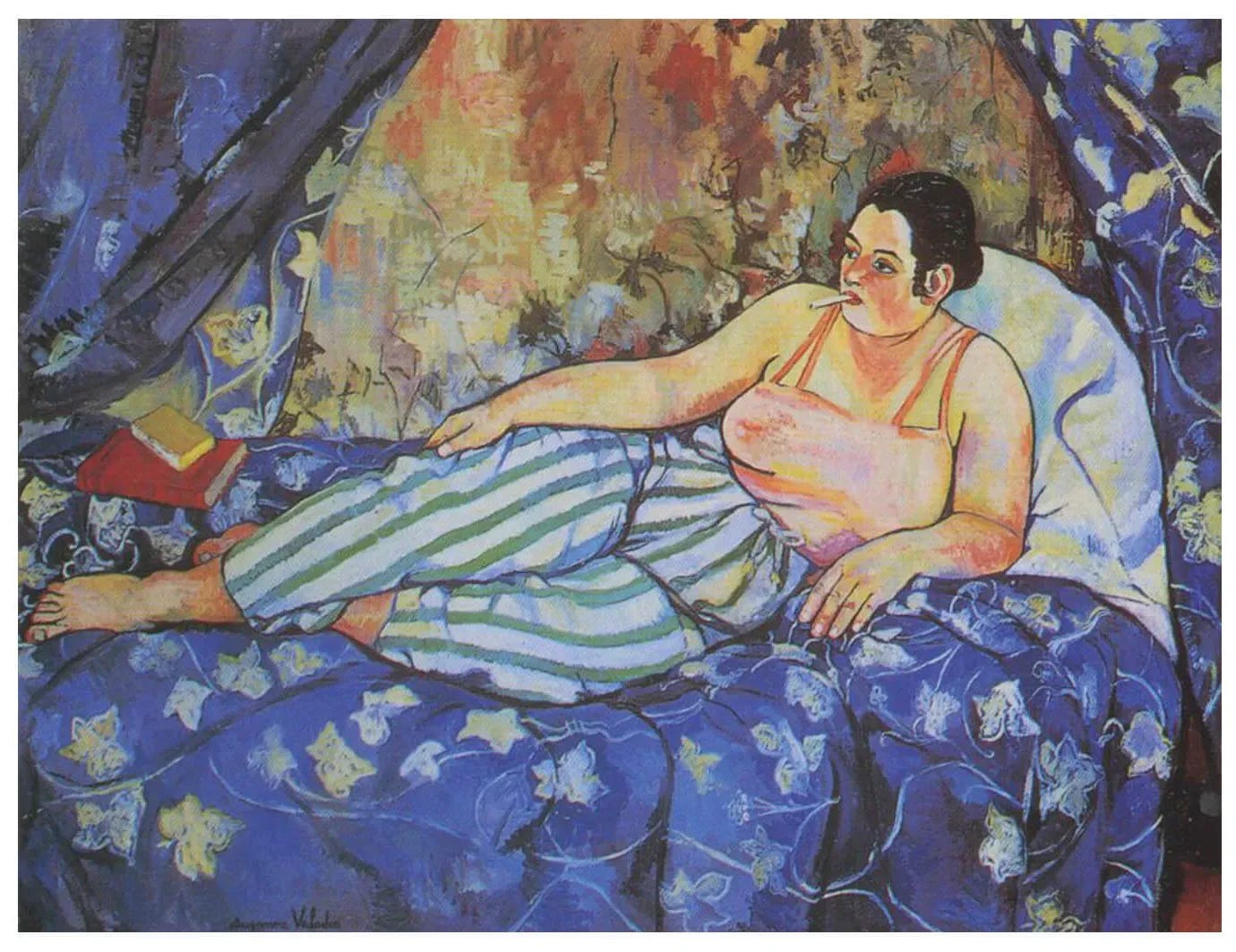

Before last autumn, I knew almost nothing about the great French painter Suzanne Valadon. No biography, nor what she looked like. Despite her acclaim, I would’ve recognised just one, maybe two of her works. I did know and love this one — ‘The Blue Room’ — no question a masterpiece.

Maybe I could’ve bullshitted you a basic gallerist’s top-line. Something like: nominally a post-impressionist (is this even true?) Suzanne Valadon’s work defied the trends and categories of her time. She pioneered painting women outside the ‘male gaze’ and, even more unusually, was a woman who painted nude men. But nothing of real background or analysis. And, for example, I didn’t yet know that Valadon was the first woman admitted to the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts. About ten years ago, I remember once referencing Valadon, to draw a parallel between her work and the self-directed Charli XCX video for her lovely pop hit ‘Boys’, which also valorises informal masculinity from a femme POV. What a phoney, dropping her name like that.

Then last year, Suzanne Valadon appeared to me twice. Unexpected, upending assumptions, suddenly impossible to ignore. First, in Ian Penman’s fascinating book Satie Three Piece Suite, an unusually structured short biography of composer and piano player Erik Satie. It turns out she was Satie’s only ever known lover. Literally, the one time we have any record of Satie having a relationship at all, it’s his super-intense six month fling with Valadon in 1893. As I’ll learn later, six months is standard for her. After she leaves him, he’s devastated. He composes ‘Vexations’ in response. Secondly, I have a powerful encounter with Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s wildly beloved ‘dances’ trio of paintings. Indirect, though it was still a punch on the nose: I’ve only seen one of these in real life, at Musée d’Orsay. The key painting lives across the Atlantic in Boston. Here it is, the incredibly familiar ‘La danse à Bougival’ (‘Dance at Bougival’) from 1883.

Of course, what I learn revisiting this artwork: the girl-woman dancing here is the seventeen year old Suzanne Valadon, by this point already a retired acrobat, a professional artist’s model, a lover (sidepiece? employee-with-benefits? sex worker?) of the forty-one year old Renoir. Thing is, when I was a child, a print of ‘La danse à Bougival’ hung in my Mum and Dad’s house, swapped out with the seasons for other ubiquitous works. Constable’s ‘The Hay Wain’, Monet’s ‘Wild Poppies’. The Renoir was the one for me, though. Too young to understand how, I was ensorcelled by luminous hotness. The gentleman dancer is not hot. She’s complying — dancing — yet gloriously disinterested in the bloke, as he leans in. I really loved that smiley chap at the table behind them too. Maybe that was me. So I now encounter Valadon as the rich backstory to an early, bewildering sort of crush. Alongside, say, Daisy Eel from the ‘Swallows and Amazons’ book Secret Water but you didn’t need to know that.

Still years away from her huge acclaim as a pioneering painter, by the time of ‘La danse à Bougival’, the teenager Suzanne Valadon had already lived several lives. More information can be gleaned about her from passing mentions in other people’s Wikipedia entries, than via her own Wiki. Similarly, from essays on male artists she encountered, if one wades through casual misogyny and moralising. I’m embarrassed too: the paintings of hers that I already loved never made me curious enough to investigate further, whereas finding out she’d had it off with Satie and was the model for Renoir’s dancing girl sent me off, spiralling, nosing through books and blog entries, on a deep dive into her early life.

Alas, Katie Hessel’s brief paragraph on Suzanne Valadon in her very successful Story Of Art Without Men is short and curiously lifeless, perhaps because Valadon is so deeply entangled in her role as muse (to men) plus, you know, all the fucking around and finding out. Hers is hardly a story of art without men, they’re bloody everywhere. Because (I admit) I haven’t yet properly read Hessel’s book, I dip in for reference, I don’t know if this is a wider flaw — in its righteous (admirable) determination to de-centralise the domineering guys, perhaps complex entanglements and relationships (toxic or fraught, or ecstatic, or all of the above) must similarly be de-centralised — or, if it’s just a momentary coincidence, just relative critical disinterest in Suzanne Valadon’s work. But whatever, dear reader, I need more, so I fall down a hole.

•

First of all there’s a rough little girl, constantly sketching, who loves horses. But nothing remotely idyllic lies here.

September 1865, she is born Marie-Clémentine Valadon, in a village near Limoges. She’ll become ‘Suzanne’ later on, courtesy Toulouse-Lautrec. She never knew her dad. Her mother Madeleine was a live-in seamstress already raising two daughters from a previous marriage. But something arising from this new pregnancy with no husband makes her situation untenable. So in the depths of January 1866, the two older girls are permanently left behind with relatives, while three-month-old Marie-Clémentine and her mum leave for Paris, travel north, move into lodgings in Montmartre. Here, Valadon will spend most of her life. Madeleine Valadon becomes a cleaner and as far as I can tell, never again contacts her family.

At five years old, Valadon and her mum survive the Siege of Paris. Surrounded by a dithering Prussian army, the starving city eats dogs and cats and sawdust bread. Paris Zoo’s two beloved elephants Castor and Pollux are butchered and sold by the slice, including in the city’s poshest restaurants. Printed menus survive that use flowery fine dining language to describe carefully prepared rat meat. Marie-Clémentine gets homegrown garden produce from nuns at her nursery. After the siege, the Paris Commune emerges in the same neighbourhood where the little girl lives with her mum — the city refuses the returning French government, instead tries to run itself along experimental lines — tries to formalise mutual aid — until the incredibly violent destruction of that movement. Twenty thousand Parisians die in what is arguably a localised civil war.

In the years after, Valadon constantly skips school to hang out unsupervised. Looking back from the end of her life, she says that as a child she located the love, excitement and ideas out on the streets of Montmartre that most children found around their family dinner table. From nine years old she is working, unwillingly, street urchin odd jobs. Helping sell vegetables from a cart. Making funeral wreaths, or cleaning. Later, waitressing. She becomes an apprentice seamstress and hates it, tries to escape, gets dragged back by her mum, beaten by the manager. By now, Madeleine Valadon is drunk and damaged, little Marie-Clémentine a feral child, near-impossible to control, but known and liked locally, mixing with everyone in Montmartre. Also, she draws pictures the whole time. There’s no discernible maternal love here: a traumatised, complex mother and daughter bond, they fight constantly, yet they’ll share a home on-and-off for sixty years.

Then at twelve years old, the girl gets a job with a livery stable, walking horses from one place to another, through busy streets. This, Marie-Clémentine Valadon loves. The horses. She turns the role into a performance: she starts dancing around them and on their backs, as she leads them, gathering a crowd with self-taught horseback acrobatics. In 1880, aged fourteen, she joins Cirque Fernando and her horse-riding acrobat schtick becomes a proper gig. Initially I thought of this as a “running away with the circus” cliché but it wasn’t like that at all: Cirque Fernando is firmly based at the bottom of Montmartre, with deep, long-standing entanglements with the 18th Arrondissement’s boho arts and leisure crowd. Outsiders, performers, street sellers, sex workers, artists. Also some superstars. That famous Edgar Degas painting of ‘Miss La La’, which in 2024 had a major exhibition built around it at the National Gallery in London, was created at this same circus, only months before the fourteen year old amateur acrobat Valadon, now calling herself ‘Maria’ would arrive to join the ensemble. Maria Valadon undoubtedly encounters Anna Olga Albertina Brown, Miss La La, a famous name in circus, a poster headliner. They’ve crossed paths years before Valadon herself will appear on Degas’ radar. It all overlaps: this circus community is part of Green Hour too.

One day, after about a year with Cirque Fernando, Valadon fills in for an absent trapeze artist and falls. Her injured spine ends her circus career.

Art history blogger Jonathan5485 writes that each morning at Place de Pigalle, young girls gather by the fountain, posing and chatting, hoping to be chosen by artists for paid modelling work. Modelling for artists means payment, means hanging out with artists, means (not always but…) sleeping with artists — it is a norm of the era that artists’ models are being hired for sex too. When she joins the hustle, Valadon is very successful, quickly in demand, making a chunk of new cash and loving a new angle on her Montmartre life.

This moment often gets written up as if it’s a huge, instant change in Maria Valadon’s lifestyle but that feels unlikely to me: this world was already her world, deeply familiar since she was a tiny child. Valadon has literally witnessed the Montmartre of the Belle Époque rise from bloody carnage and rubble, through her teens, all around her, shaping the streets she played and worked on. She is right at its heart, in a way that most other artists are not. Artists arrive deliberately to be a part of something. She was a part of it already, as she became conscious. Polite society is judgey but polite society itself was brutally ruptured less than a decade before. Shining a modern lens on her teens, surely it must’ve been complex (and gradual and visceral) more than any clear dividing line understanding of where work — or artistry, or romantic love, or self-aware sex work — or any other aspects of daily life — began or ended. You model in daytime, join the Green Hour at dusk, party into the night, and everyone else is there, partying too. You’ve known so many of these people your whole life.

In potted biographies, focused on men, relationships are casually described as ‘they become lovers’ or ‘they have an affair’ without any nod to the sheer scale of discrepancy in wealth and power, nor the contracted starting point of an hour-by-hour employment as a model, nor any widescreen sense of broader context — all of this is a transactional, performative normalcy. Which is to say, looking back from here, now, can we truly know if, where, when modelling work becomes sex work, where sex work ends (or doesn’t end) and romantic love begins (or doesn’t begin but is performed)? Also, if any of that matters, to the protagonists’ art-making, or their life?

Like, at seventeen, Valadon is modelling for Pierre Puvis de Chavannes at his studio in Neuilly. His vast apartments dazzle her. His wealth feels royal. She moves in with him, and their ‘love affair’ lasts six months, before ending (it seems) cordially. No drama. They stay friendly enough afterwards that she’ll go back and model for him occasionally. Paid work. So, ‘client’ and ‘hire’, both before and after being romantic partners. A dizzying difference in wealth and access and resources. And also, inevitably, Pierre Puvis is forty years older — fifty-seven when Valadon turns seventeen.

She also models for Berthe Morisot, who is almost unique at the time: both a mother and a professional working artist. Morisot uses Maria for a painting of a girl on a high wire. I wish I knew more about their encounters. It would be great — a chunk of the story that passes the Bechdel Test. Given that Valadon herself will become a professional woman artist, while already a mother, it’s reasonable to imagine that she first comprehended that as a possibility via Morisot.

In 1883 Maria Valadon will turn eighteen. This is the year she hooks up with Pierre-Auguste Renoir, who is forty-two. He’s back in Paris after some world travel, already successful and selling work. He is with long-term girlfriend Aline Charigot, who he’ll marry a few years later. But he’s seen out and about with Valadon, day and night, strolling and dancing. Renoir is commissioned by art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel to paint the ‘dances’ trio of works: ‘Danse à la ville’ (‘Dance in the city’), ’La danse à Bougival’ (‘Dance at Bougival’) and ‘Danse à la campagne’ (‘Dance in the Country’). They’re big. Each painting is a life-size couple dancing in a contrasting setting. The first two paintings — ‘city’ and ‘Bougival’ — feature Valadon as the woman dancer, diffident, looking away from the viewer. The final painting — ‘country’ — swaps out Valadon as model for Aline Charigot instead, who looks directly out at us, smiling. One can see the temptation to make psychosexual signifiers of the triptych.

That summer, Renoir takes Valadon on holiday to Guernsey, paints a nude of her that he destroys later, learns that Charigot is on her way to the island, and immediately sends Valadon home, so she’s gone before Charigot arrives. At the same time, Valadon is actually pregnant, she got knocked up some time around April, and won’t tell friends or her mum who the father is. She makes a flirty game of it but won’t give up a name. Or, she’s unsure. She’s been seeing a Catalan lad from Barcelona, a sweet, serious student close to her own age, Miquel Utrillo. Seven years later, back in Paris, Utrillo will be persuaded to sign a document accepting paternity, though few accounts believe he was actually the father. The child will get his surname. We don’t know why he signs. Actually, the Maria Valadon of the Green Hour has a tumbling pile of overlapping lovers. Another possible father is Adrian Boissy, a drunk who works in insurance, who takes her home one night from the club and rapes her.

When pregnancy interrupts her paid modelling, it turns out she’s gained a mystery benefactor — the dad, or the dad’s family? — so she doesn’t need to work for a time. On Boxing Day she gives birth to her son, Maurice, justifying the name by telling friends she hadn’t had any man called Maurice, so no-one can make a false connection. Maurice will go on to have a troubled life, with awful struggles with mental health and long-term alcoholism. But he’ll also achieve great success as an artist in his own right, through the first half of the twentieth century. In fact, he’ll be famous enough it will arguably stifle recognition of his own mother’s (far greater) genius, until much later on. Much of their careers will get marketed hand-in-hand, to her (temporary) detriment.

The oldest surviving signed and dated Valadon sketch is also from 1883. For the next decade she’ll still produce drawings and won’t paint seriously until 1893. She won’t be a full-time professional painter until 1896. That bastard Renoir belittles her sketching and discourages her art. She continues with her artistic ambitions despite Renoir, though of course, proximity to his (and many other artists’) processes and techniques must have been very useful. Like working on a film set when your ambition is to direct. Again, after they’ve split up, still she gets hired as Renoir’s model sometimes. Needs must. Three years later, after she’s become ‘Suzanne’, has her two-year-old child, and after Renoir has had a baby with Aline Charigot, still he’ll complete his unabashedly horny portrait, ‘The Ponytail’.

While lost in trying to write this thing, I’m reading a great book from 2023 about parallels (and entanglements) between selling art and selling sex, Working Girl, by Sophia Giovannitti. It’s a brilliant, thought-provoking essay by someone who experiences today’s commercial art world at first hand, who has also done professional sex work and is unafraid to document it, and who merges the two successfully, exposing and exploring the grey areas. Early on in this, I wanted to make the (fairly obvious) point about how often it is, even today, with an important artist who is a woman, that we’ll first encounter her as a model and muse to men. Lee Miller, currently at Tate Britain, with her modelling career before all else, and her time with May Ray. Or that devastating early press quote about Frida Kahlo: “Mrs Diego Rivera can and does do very passable portraits.” Then reading Giovannitti, she made the same point in passing, giving an example I hadn’t considered: Leonora Carrington and her relationship to Max Ernst. There’s loads more.

Giovannitti is very clear-sighted and educative for someone like me, about understanding slippery but graspable differences between romantic intimacy, and sex as labour, and a multitude of other kinds of sex. She writes:

Selling sex hasn’t impacted what sex itself is to me, any more than any other sexual experience I’ve had; which is to say, of course it has impacted me, but in no unique way. My own sex work has had an equal effect on my sex life as the first person who begged me for head, in high school, citing Kierkegaard’s leap of faith as a reason to give it up.

Bravo. A terrific closing gag and a real clarity, both at once. She goes on:

The same goes for making and selling art and writing. I can discern for myself what is meaningful and what is bullshit; what I make that I care deeply about and what I make that is for money alone.

Up to now, these artists (older men) in Valadon’s life — employers of her casual labour, also ‘lovers’ — have tended not to encourage her own work. But when Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec shows up, moving into the flat upstairs, roughly her own age (just ten months older) and not yet famous but fast becoming acclaimed, it is his fierce friendship and encouragement that will drive her to success. They’ll still be lovers but this time it feels more like peers. It’s 1885, so Valadon is almost twenty, with a baby son. I’ll resist a massive sidebar on Toulouse-Lautrec — he must’ve been such killer company, the witty aristo gone rogue, supremely talented, sex-fuelled, yet convivial rather than predatory, also a life-long outsider, through living with his disproportionate dwarfism. Prejudice there is sharp. Even relatively recent accounts go on at length, lasciviously othering his appearance.

First, she becomes the vivacious, sharp-tongued co-host of Toulouse-Lautrec’s sprawling house parties. Then, she becomes ‘Suzanne’. He literally gives her her name. To this point, Valadon has been Marie-Clémentine, then just ‘Maria’. But Toulouse-Lautrec pinpoints her uncomfortably when he nicknames her ‘Suzanne’ after ‘Susanna and the Elders’, the apocryphal non canon Biblical story from the ‘Book of Daniel’. This is the tale of a woman who gets spied on and falsely accused of adultery by lecherous judges, trying to blackmail her. She’s rescued by the book’s young prophet Daniel, who exposes their lies. They get executed and ‘Susanna’ is vindicated.

The starting point of this ‘Susanna’ becoming the adopted name for the former Marie-Clémentine is — obviously — that she’s been hanging around with loads of horrible old artist pervs who don’t appreciate her, just want the sex. The name is a joke on that normalcy. Perhaps Toulouse-Lautrec isn’t bothered about the detail, just digs the gag of dissing the older generation of artists. Or perhaps he fancies himself as a bit of a ‘Daniel’ and sees himself as Valadon’s rescuer — he appreciates her as a person, closer to a bona fide friend, instead of just giving him the horn. Anyway, whatever, she takes on the name and it sticks. Toulouse-Lautrec encourages and valorises Valadon’s work, defines her as artist. He’s her first buyer. More than that, the first ever painting (rather than sketch work) she completes, she gives to Toulouse-Lautrec and signs it ‘Suzanne’.

This is a longer love affair and has a sense of being organic. She breaks her six month rule. And, of course, she keeps the public name ‘Suzanne’ for life. He doesn’t pay her to model but is an enormous support in other ways. Accounts including Gilles Neret’s Taschen book on Toulouse-Lautrec from 1999 say that she was in love and wanted to marry him.

When Toulouse-Lautrec paints her, he defines her, literally: ‘Portrait Of The Artist, Suzanne Valadon’, the respect shown in the title. Most importantly of all, he sends her off, not as model but clutching a folder of her best sketches, to his friend Edgar Degas, who is at this point in his early fifties.

Last autumn, I was chatting to a client who is a terrific artistic practitioner across multiple disciplines, in music and words, as well as constantly craft-making and arts experimentation. In the process of reassuring her about the value of a particular piece of practice, I casually — even slightly self-mockingly, though I also felt it deeply — said: “but, you’re one of us.” A firm full-stop. Unexpectedly, her reaction was strong — she was moved by that statement. I hadn’t placed any significance on the framing, though of course I should’ve done. Later on, I remembered the scene in The West Wing where outgoing speechwriter Sam Seaborn has sent a note to comms chief Toby Ziegler, carried by Will Bailey, recommending him for a job: “Toby, he’s one of us.” Since that conversation, I’ve thought about it a lot. Us and them. The essay I wrote in a previous Border Crossing about creativity and artistry was probably rooted in those thoughts. I’m not there yet.

Then this week: after he looks at her sketches, Degas says to Suzanne Valadon “Yes, it is true. You are one of us.” She won’t ever forget it.

For Suzanne Valadon, she adores his work and it’s mutual, Degas is a master, also the single great gate-opener for her artistic career. Their friendship will last many years, they correspond and she’ll remain a regular visitor to his apartments, swapping advice and connections for gossip about the Montmartre scene. He writes to her every so often, asking her to visit with artworks to show him. Having been gregarious in his youth, this Degas is by now isolated at home. He’s a grump, was always a bit prejudiced, but has gathered strident antisemitic opinions since the Dreyfuss Affair. So he’s pissed off a lot of old friends, Renoir included. I don’t know if Suzanne Valadon shares his views, or loves him despite them, or (most likely) doesn’t care. So here we have a friendship that almost certainly is never sexual, and where the transaction is informal and not financial, and it lasts. She never models for Degas, I don’t think.

Writing this has made me ache for my wasted youth, in a way I almost never do.

Erik Satie comes later. Outside my self-imposed restriction of writing about Valadon as a teenager, despite their love affair being the inspiration for this essay. They meet in January 1893. Valadon is in her late twenties, Satie eight months younger. Ian Penman calls her ‘woman’ and him ‘boy’ — and that seems right. Penman calls her a former ‘high wire artiste’ presumably because of Morisot’s painting, though I haven’t spotted the high wire mentioned in accounts of her circus life, he’s probably right there too, figuratively if not literally. He describes this affair as the “one thing in Satie’s life that doesn’t fit, according to everything else we know about him.”

From her POV, Satie is Suzanne Valadon’s last romantic adventure, before she’s persuaded to marry into the bourgeoisie, before her artmaking professionalises, and her life settles down for a time. Intriguingly, it’s her only affair mentioned in a surprisingly chaste ‘Personal life’ section of her own Wiki entry. Perhaps because Satie acknowledges it far more openly than most of the men. He’s working as a back-up piano player at Le Chat Noir. They meet clubbing and for Satie it’s love at first sleepover — he asks her to marry him the morning after the night they met. She says no, but moves in next door. She’s already been seeing Paul Mousis for three months — a stockbroker, a wealthy patron, a hanger-on of the Green Hour, who likes buying drinks for starving artists. Valadon has only been painting for a year or so but she’s getting somewhere and racking up admirers. Really, the 1890s will be the decade when she ‘makes it’ as an artist and this drama is mere distraction. Her affair with Satie is an angry green triangle. Both men openly compete: Mousis often trying to win her back (while seeing other women).

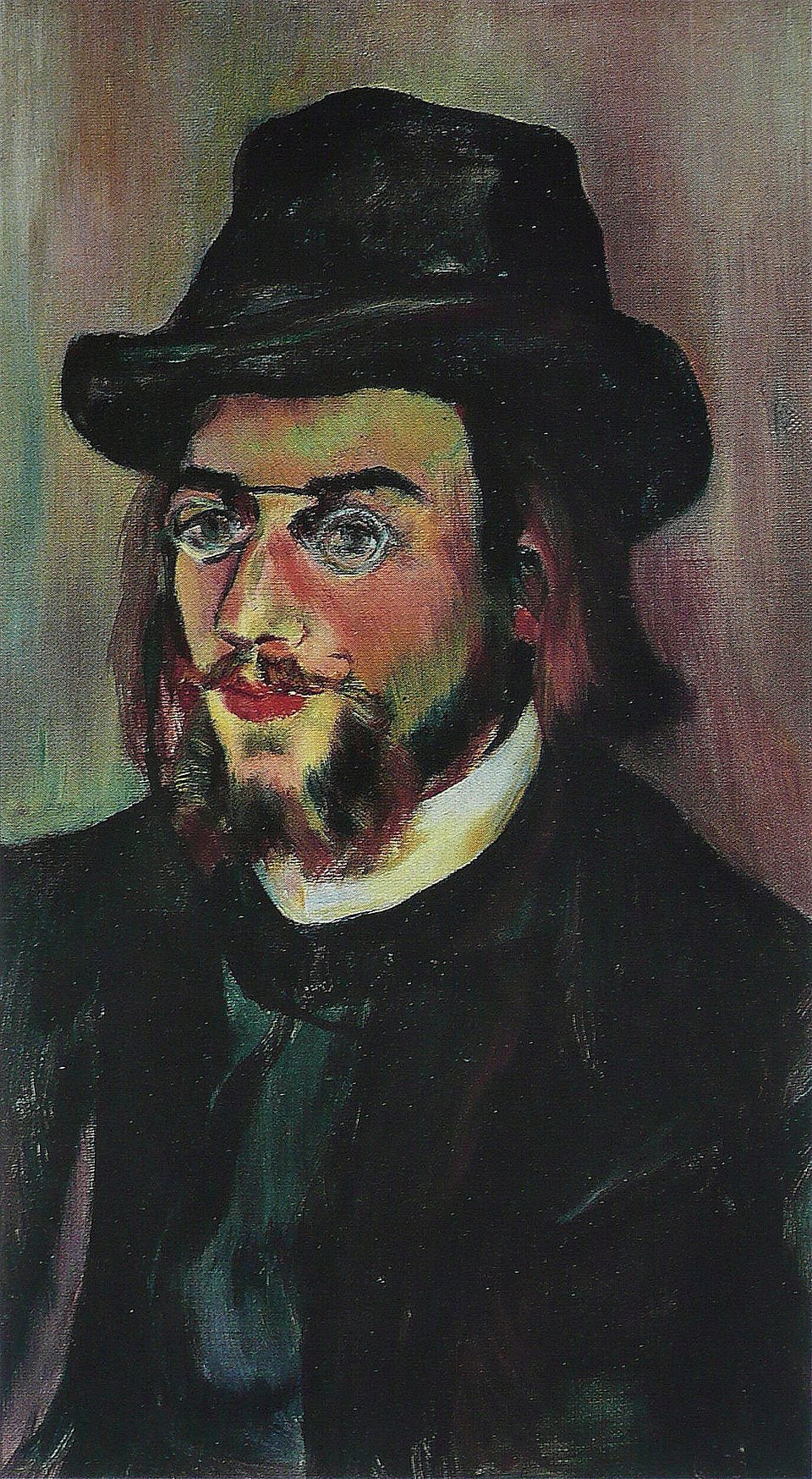

Crucially, Valadon paints Satie. One of the most arresting, least buttoned-up, images of a musician who valued control of his image, capturing the earlier Montmartre scruffy edge to his careful (infamous) style.

This man is hot. She inspires several of his compositions. The affair lasts (again) roughly six months, before she goes back to Paul Mousis. But their breakup wholly devastates Satie. It’s the trigger for his ‘Vexations’, a short, broken composition. He doesn’t bother specifying it’s for piano on the score (though it is) however he writes instructions about how you need to prepare, carefully, to repeat the piece 840 times. It has been performed a great deal but almost nobody has managed 840 rounds. It’s rumoured to be cursed. Satie will never love again.

I’ll stop there.

Valadon’s life doesn’t get less interesting with maturity and marriages. Turmoil persists and obviously it’s a chaotic era. But from here on, she is mostly financially stable and her reputation as a painter will constantly increase. Art will be her lifelong vocation. One thing I’ll mention: her second husband André Utter is almost two decades younger than her. They’ll meet in 1909 through her now grown-up son Maurice. She’ll begin an affair with Utter after he models for her. The old switcheroo. In fact, he is her first male nude model, playing ‘Adam’ to her ‘Eve’ in a painting where they stand parallel, faced outwards, not looking at each-other. She’s still married to Mousis, though that’s rapidly sliding. She misses Montmartre and Green Hour too much, and her route to taking a young lover begins by having him pose for her.

For me, as you can tell by the amount of time and mind-space this has swallowed, I’m plain overwhelmed to know that Valadon was that diffident girl dancing in Renoir’s painting, even just to compare it to how Toulouse-Lautrec painted her, and how she painted herself. Her paintings are outstanding. She is their equal.

•

get in touch

email me: chris@christt.com

Instagram: cjthorpetracey

always there

• Check out my Double Chorus newsletter on songwriting and the business of music.

• If your creativity could benefit from a conversation to help re-balance it with the rest of your daily life, check out my face-to-face sessions. I’m working on a proper website for this asap but for now, details are just via a page on here and prices aren’t going up yet.

• Listen to series eight of Refigure podcast, the fun bitesize arts review show I make with Rifa.

• Two classic Chris T-T albums London Is Sinking (2003) and 9 Red Songs (2005) for the first time on 12” vinyl limited stocks still available.

• Later albums made for Xtra Mile Recordings, Love Is Not Rescue (2010), The Bear (2013), 9 Green Songs (2016) and Best of Chris T-T (double CD, 2017) are now available on CD with limited stocks on Bandcamp.

• Check out the Border Crossing Press shop.

• My Pact Coffee discount code is CHRIS-A8UKQG. Sign up for beautiful coffee bean delivery, use this code, you get £5 off and I get £5 off a bag.

Thanks again. Please look after yourself and your people.

all my love,

Chris

x

Brilliant writing, Chris.